Fungus Gnats

Damage

Fungus gnats (Bradysia spp.) larvae are considered as one of the most damaging pests of both indoors and greenhouse plants. The larval stages (maggots) of fungus gnats cause direct damage by feeding on roots of plants whereas their adult flies (Photo 1) cause indirect damage by disseminating disease causing fungal spores from plant to plant as they disperse through the greenhouse. The maggots primarily feed on fungi and organic matter but they can also cause a serious damage to many ornamental plants. Maggots often chew or strip plant roots and tunnel stems affecting water and nutrient absorption in severely injured plants resulting in lost vigor, turn off-color and eventually death. During feeding maggots also transmit fungal pathogens like Fusarium, Phoma, Pythium and Verticillium. Adult flies are also nuisance to people and employees.

Photo 1. Fungus Gnat Fly

Facts (show all)

- Taxonomy

-

- Common name: fungus gnats

- Scientific name: Bradysia coprophila

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Arthropoda

- Class: Insecta

- Order: Diptera

- Superfamily: Sciaroidea

- Family: Sciaridae

- Genus: Bradysia

- Species: Several including B. coprophila, B. difformis, B. impatiens, B. odoriphaga

- Identification

-

Adults: Adults of fungus gnats are tiny about 3-4 mm long, blackish to grayish in colored flies with clear wings. They look like small mosquitoes with long slender legs and segmented antennae. Adults are attracted to light but generally you find them flying around potted plants especially near to potting media and compost.

Eggs: Eggs of fungus gnats are tiny translucent and oval in shape.

Larvae/maggots: Fungus gnat maggots (larvae) are legless, whitish in color with black head capsules. These larvae found just 1-2 inch under the surface of the potting medium/soil.

Pupae: Pupae of fungus gnats are oblong.

- Biology

-

The life cycle of fungus gnats consists of four developing stages including eggs, larvae, pupae and adult flies. Females of fungus gnats often lay over 1000 eggs in their lifetime on the media surface. These eggs hatch within 3- 4 days at 75F into small larvae (also called maggots) that develop through four stages (instars). Depending upon the temperature, maggots mature within 10 days after hatching from eggs and then pupate in the potting medium/soil. Adult flies emerge from pupae within 4-5 days. Thus egg-to-egg life cycle of fungus gnats is completed within 20-25 days at 20-25C.

- Biological control

-

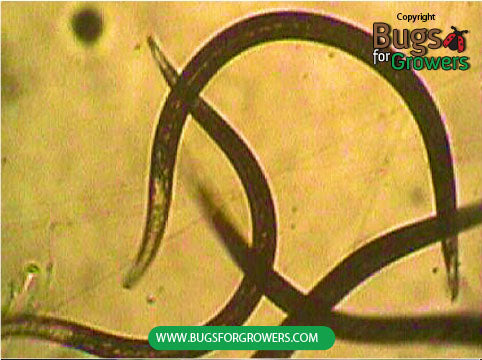

Continuous and overlapping generations of fungus gnats in the greenhouse have made most control strategies difficult. Currently, most growers rely on insecticides to manage fungus gnats in floriculture. However, use of these insecticides is restricted due to their environmental pollution and human health concerns, development of resistance to pesticides and removal of some of the most effective products from the market. Biological control agents including Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), the predatory mite, Hypoaspis miles and beneficial entomopathogenic nematodes like Heterorhabditis bacteriophora, Heterorhabditis indica and Steinernema feltiae have been used as alternatives to chemical pesticides for the effective control of fungus gnat larvae in both indoors and greenhouses. All three species of beneficial nematodes and predatory are commercially available. Beneficial nematodes can be applied at the rate of 1 billion nematodes per acre for the effective control of fungus gnats.

- Beneficial predatory mites

-

- Predatory mite, Hypoaspis miles (Stratiolaelaps scimituse)

- Beneficial entomopathogenic nematodes

-

- Heterorhabditis bacteriophora

- Heterorhabditis indica

- Steinernema feltiae

- Research Papers

-

Chambers, R.J., Wright, E.M., Lind, R.J., 1993. Biological control of glasshouse sciarid larvae (Bradysia spp.) with the predatory mite, Hypoaspis miles on Cyclamen and Poinsettia. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 3: 285-293.

Gillespie, D.R., Menzies, J.G., 1993. Fungus gnat vector Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicislycopersici. Ann. Appl. Biol. 123: 539-544.

Gouge, D.H., Hague, N.G.M., 1994. Control of sciarids in glass and propagation houses with Steinernema feltiae. Brighton Crop Protection Conference: Pest Dis. 3: 1073-1078.

Gouge, D.H., Hague, N.G.M., 1995. Glasshouse control of fungus gnats, Bradysia paupera, on fuchsias by Steinernema feltiae. Fundamental and Applied Nematology 18: 77-80.

Harris, M.A., Oetting, R.D., Gardner, W.A., 1995. Use of entomopathogenic nematodes and new monitoring technique for control of fungus gnats, Bradysia coprophila (Diptera: Sciaridae), in floriculture. Biological Control 5: 412-418.

Jagdale, G. B., Casey, M. L., Grewal, P. S. and Lindquist, R. K. 2004. Application rate and timing, potting medium and host plant on the efficacy of Steinernema feltiae against the fungus gnat, Bradysia coprophila, in floriculture. Biol. Contrl. 29: 296-305.

Jagdale, G. B., Casey, M. L., Grewal, P. S. and Luis Cañas. 2007. Effect of entomopathogenic nematode species, split application and potting medium on the control of the fungus gnat, Bradysia difformis (Diptera: Sciaridae), in the greenhouse at alternating cold and warm temperatures. Biol. Control. 43: 23-30.

Kim, H.H., Choo, H.Y., Kaya, H.K., Lee, D.W., Lee, S.M., Jeon, H.Y., 2004. Steinernema carpocapsae (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) as a biological control agent against the fungus gnat Bradysia agrestis (Diptera: Sciaridae) in propogation houses. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 14: 171-183.

Lindquist R., Piatkowski J. 1993. Evaluation of entomopathogenic nematodes for control of fungus gnat larvae. Bull. Int. Organiz. Biol. Integr. Control Noxious Animals and Plants. 16: 97-100.

Tomalak, M., Piggott, S. and Jagdale, G. B. 2005. Glasshouse applications. In: Nematodes As Biocontrol Agents. Grewal, P.S. Ehlers, R.-U., Shapiro-Ilan, D. (eds.). CAB publishing, CAB International, Oxon. Pp 147-166.

Wilkinson, J.D., Daugherty, D.M., 1970. Comparative development of Bradysia impatiens (Diptera: Sciaridae) under constant and variable temperatures. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 63: 1079-1083.